A legend of the pool and hero on the Western Front

Last year, in his first Remembrance Day commemorative address, Governor-General David Hurley spoke about the life of Australian swimming champion Cecil Healy.

Healy is the only Australian Olympic gold medallist to be killed on the battlefield. He was a legend of the pool and a hero on the Western Front.

Remembered for many things, Healy’s morality is a trait that stands out and it was never more evident than in his unbelievable show of sportsmanship at the 1912 Stockholm Olympic Games.

His is an incredible story.

Photo credit: David Wilson

A story that needed to be told

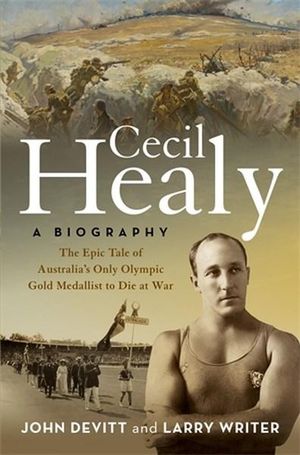

Last year, Larry Writer co-authored ‘Cecil Healy – A Biography’ with Australian Olympic gold medallist John Devitt. The book would go on to win the 2019 Nib Military History Prize.

“John Devitt had long known about Cecil, although he was born 18 years after he died,” says Writer. “They had a lot in common: both were involved in controversial 100 metre Olympic swimming finals, both lived in Manly, both were devout Catholics. He developed a strong affinity.”

“John asked me: ‘I’m writing about Cecil Healy but how do you do it?’” says Writer. “I agreed to be kind of a guide. It turned out to be a full-time job for the next four years!”

Research for the book took Writer and Devitt to the UK and across Europe, including the site where Healy would ultimately be killed in action. Along the battlefields of northern France and following the route of the Somme River, they were led by David Wilson – an army veteran, author, battlefield guide and historian at the Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney.

“I had mentioned Cecil in my book on the 19th Battalion. I knew the place where he was killed,” says Wilson. “I joined Larry and John on the Somme and we spent a week there. We tracked the AIF in general but I then took them to places specifically associated with Cecil. We tracked his journey from Amiens and I took them to all of the places where the unit stopped, including where Healy spent his last night. We followed the route of Cecil Healy’s last week on earth.”

A legend of the pool and surf

Larry Writer describes Cecil Healy as a swimming champion during a great era for the sport.

“Cecil came to prominence in 1896-97 as a youngster. He soon established himself as the fastest swimmer in Australia across 100 yards,” says Writer. “Swimming was an enormous spectator sport at the time. There would be capacity crowds at Woolloomooloo and Balmain. At some venues you might get eight to nine thousand people watching. There would be people in trees and on rocks and all around.”

Healy’s legendary surf lifesaving feats ran concurrently with his career in the pool. “On moving to Manly in 1907, he became a champion at surf carnivals and there were seven or eight occasions recorded of him saving lives,” says Writer. David Wilson agrees. “Healy knew the area and tides and that people were going into the water not knowing what they were getting themselves into,” says Wilson. “He and his friends arranged surf patrols on beaches and saw it as a moral responsibility to their community.”

In the pool, and swimming with his new ‘crawl’ technique, in 1904 Healy swam the fastest ever time in the 100 yards freestyle and was Australasian Champion in 1905 in the 110 yards freestyle. He made the Intercalated Olympic Games of Athens 1906, winning a bronze medal, though was not able to get the funds together to go to the 1908 Olympic Games in London.

Undeterred – and after having dedicated himself to his work as a salesman and journalist – Healy kept at it and won Australian titles in 1909 and 1910. He went on to qualify for, and go to, the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm.

Photo credit: David Wilson

A chance at gold

Governor-General David Hurley agreed that it was “the greatest act of sportsmanship in Olympic history.”

At the 1912 Olympic Games, Healy and fellow Australian Bill Longworth came through the first semi-final of the 100 metres, qualifying for the final. However, a mix up in timing meant that the Americans, who were supposed to attempt to qualify in the second semi-final, didn’t show up.

That meant that the overwhelming race favourite, Duke Kahanamoku, was ruled out of racing in the final.

“Healy made the 100 metres final but his times were very much second to Duke Kahanamoku’s, an American from Hawaii,” says Writer. However, insisting that to win without Duke in the race would be a hollow victory, Healy lobbied for Duke and the Americans to be given the chance to qualify. Healy refused to race if Duke wasn’t allowed a shot at making the final.

“He and others mounted a vigorous campaign of complaint to the Olympic committee,” says David Wilson.

The Olympic committee relented, and Duke went on to qualify and win the final, with Healy finishing second.

“It was an amazing act of sportsmanship. He did himself out of a gold medal,” says Writer. “Cecil had a terrific conscience, which came into play again during the war years.

In their biography, Devitt and Writer describe that “Healy’s gesture cost him victory but earned him a place in sport’s pantheon of true champions.”

Nonetheless, Healy would go on to claim a gold medal at the Games as part of the 4×200 metres Australian relay team, beating an American team anchored by Duke.

A lasting friendship

On the podium after the 100 metres final, Duke Kahanamoku held up Healy’s arm and claimed that he was the true Olympic champion.

A couple of years later, in 1914, Healy would be instrumental in convincing Duke, a pioneer of surfing, to come to Australia to show off his wooden board riding.

“Board riding was very much a novelty at that stage,” says Writer. “Duke helped it take off in Australia and thousands of people came to the beaches in NSW and Queensland to watch.”

Photo credit: David Wilson

A hero

In 1915, at age 33, Healy enlisted and joined the war as a Quartermaster Sergeant.

In 1917, he decided to undertake officer training at Cambridge to become an infantry platoon commander and go to the frontline.

“His conscience would come into it again,” says Writer. “Healy started thinking that ‘it’s unfair, I can’t sit back in safety while my friends put their lives on the line on the frontline.’ He knew exactly what he was getting into. He had seen so many friends who had died and been wounded. Letters that he sent home were quite fatalistic. He knew that he may not be coming back.”

“I believe that it was his Jesuit education that drove Cecil,” says David Wilson. “I believe he had a moral fibre that was guided by his background, religion and Jesuit education. It was his fundamental personal philosophy. He couldn’t let other people do things that he couldn’t do himself.”

Healy died a hero, leading his men in action on the battlefield on 29 August 1918 as part of the 19th Battalion, 5th Brigade, a mainly NSW formation. Healy and several of his men were cut down by German machine-gunners near Sword Wood on the western side of the Somme. Healy’s platoon objective had been to clear the Germans out of one of the many defensive positions protecting the approaches to Mont St Quentin, ground dominating the strategically important town of Peronne.

Two days after Healy died, on 31 August, his battalion was one of those that famously achieved the objective of capturing Mont St Quentin.

A legacy

Healy’s body is now buried at Assevillers Commonwealth War Cemetery, about 10 kilometres west of Peronne. The town has adopted Healy and in the town square there stands a statue of him, dedicated in 2018. While touring the battlefront doing research for the book, John Devitt sprinkled sand that he had brought from Manly Beach on Healy’s grave and a local Catholic deacon then said prayers.

On what made him dedicate so much time and energy to telling Cecil Healy’s story, Larry Writer reflects that writing the book was about the experience, fulfilling John Devitt’s dream and remembering Healy’s life.

There were many highlights along the way. “Getting to know more about those incredible swimming events and lives of these young swimmers. Duke was pretty compelling stuff too. I was hooked by them,” says Writer. “When Cecil was at Cambridge he wrote for the Forces magazine. It showed me a side of Cambridge that I had no idea about. But the icing was getting to tour the battlefields with David Wilson. What we did with David was get an appreciation of all the people from all the nations fighting that terrible war. Nobody had a mortgage on bravery.”

“Cecil was a fantastic guy,” says Writer. “A truly wonderful fellow.”

Governor-General David Hurley’s closing remarks on Remembrance Day 2019 about Cecil Healy were as follows:

‘Cecil Healy had no love of the military, no desire to fight, but he recognised that his values and his freedom were threatened. Reluctantly he chose to serve, fully understanding the risks contained in that decision.

In that, he is an example to us today. In that, we should be forever grateful to the thousands of men and women like Cecil who we remember today.

Lest We Forget.’

Our sincere thanks and appreciation go to Larry Writer and David Wilson for their generosity and time, to John Devitt for his inspiration, to the Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney for their support and finally to Cecil Healy for his courage and sacrifice.

*****

Especially during these difficult times, please make sure you reach out to the following organisations if you or someone you know is in need of mental health support: Open Arms (1800 011 046), Beyond Blue (1300 22 4636) and Lifeline (13 11 14).